When I was growing up, my heroes wore capes, tights and face masks. They had bulging muscles, square jaws and respectable day jobs. There wasn’t much variety in our role models for saving the world. I am still full of admiration for Clark Kent, Peter Parker and the like, not just for rescuing the innocent from the dastardly villains but also for inspiring children to want to do good, for no other reason than it being the right thing to do.

But for all their glory, the cape-wearing heroes of my youth have been sidelined by a new, far more impressive champion. Every day for weeks, my social media feed has been full of clips of a 16-year-old girl with Asperger syndrome, taking on adults to save the world.

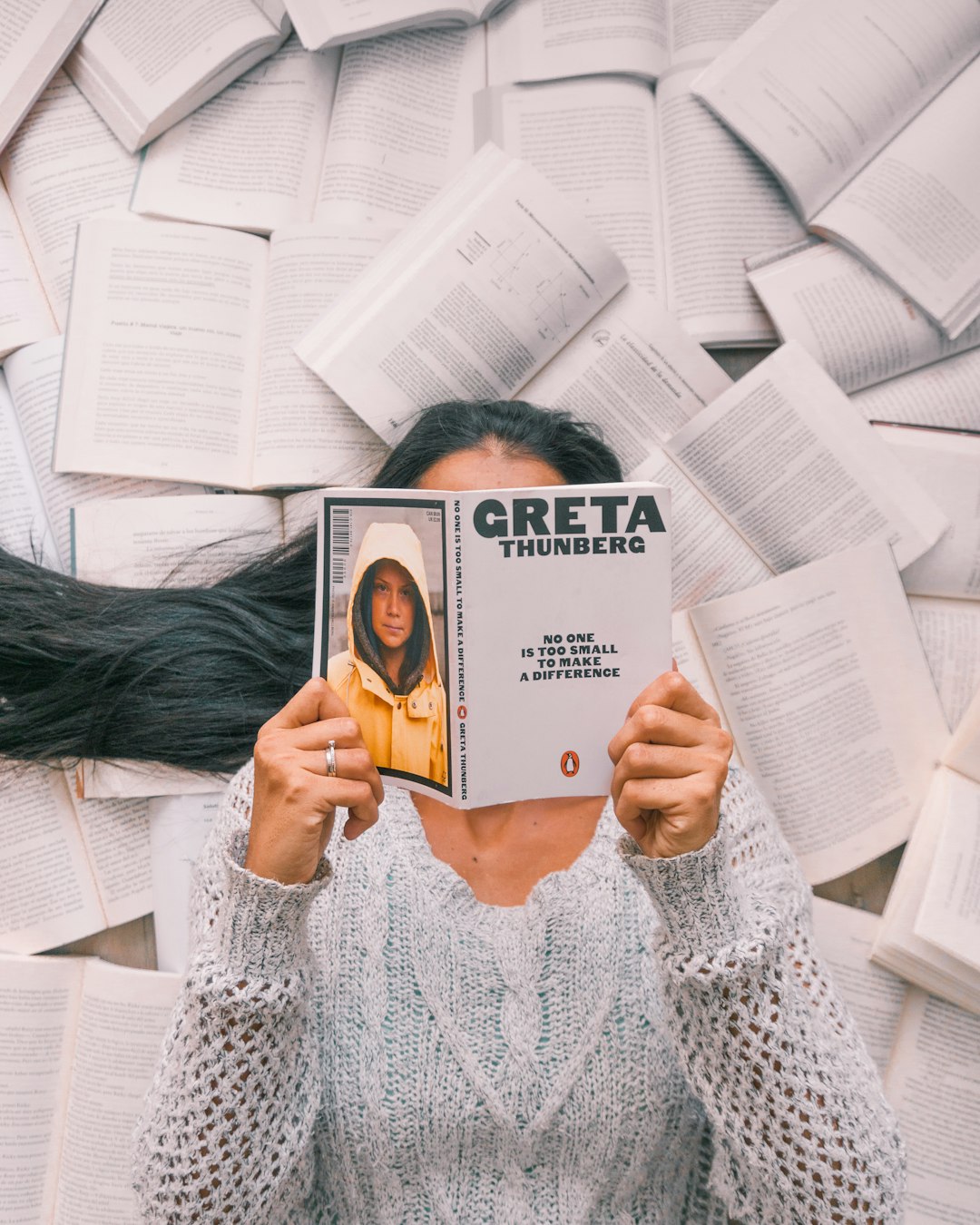

At the time of writing, nearly one million people have watched the YouTube clip of Greta Thunberg on The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, in which she tells us it is time to take a stand against climate change. On Friday, an estimated four million joined her cause by marching in cities worldwide in a global climate strike. In New York, where Ms Thunberg herself led the charge, the city’s 1.1m public school pupils were given leave to join her. The teenager has inspired millions around the world, starting with a younger generation but quickly transcending the generational gap. Her message is simple: to fight for the good of all mankind.

So why are there so many people trying to put her down? It is not her peers shouting names in a schoolyard; it is adults, politicians and public figures. Among the most visible detractors who have publicly attacked Ms Thunberg are high-profile businessmen, politicians and columnists. They do not only attack her reason for speaking out, but publicly deride her on a personal level.

Whether Ms Thunberg has sparked the global climate revolution that will save the ice caps remains to be seen. But by simply being in the public eye, she has changed the definition of a hero. She has shown us that anyone can be an instigator of change, a voice of reason and a saviour of humankind. You don’t need the muscles and the cape. Of course, most of us know that intellectually but we can all benefit from seeing someone we can identify with achieving if not the impossible, then at least the improbable.

I remember watching a Ted talk by the wonderful Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie about the danger of a single story. She said she started off writing stories about blond children playing in the snow and drinking ginger beer, because that is all she had experienced in the English and American books she grew up reading. Her single story about books at that time was that protagonists had to be apple-eating, rosy-cheeked Enid Blyton characters.

With time, Adichie discovered African writers and realised her own world was just as valid a subject matter as any. She has gone on to become one of the most celebrated African novelists in modern time, and she has given us some unforgettably complex and deeply human Nigerian characters. These will become the benchmark for future readers, who will not have to doubt if their own experience is worthy of committing to paper.

Australian author Graeme Simsion did the same for people with Asperger’s with his enchanting, romantic-comedic novel The Rosie Project. In a category of fiction where the protagonist is usually a tall, dark and handsome alpha male, the novel’s socially awkward Don Tilman is a breath of fresh air. Simsion deliberately never described his character as having Asperger’s but his empathetic depiction earned praise from autism groups. As the author said: “There’s a lot of Don Tilmans like that out there.”

Sarai Walker’s hilarious novel Dietland gives us a heroine impossible to ignore, not just because she weighs 300lbs but because she stops trying to hide her weight or make excuses for her size. She boldly takes her place in a world of size zero models, in a novel with themes exposing body-shaming and misogyny. By the end of the book, she remains a weighty character in more ways than one, having challenged societal concepts of conforming.

We need more than a single story to give us hope, whether it is about a different kind of hero, an alternative love interest in a romantic comedy, or the unexpected achiever in a corporate success story. We all deserve to see ourselves represented, both in fiction and in real life.

The diversity I see in both fictional characters and real-life role models is growing exponentially, and it is about time. And since stories transcend the medium of literature, we need this diversity to take hold on stage and screen too. The human experience is not limited to one skin colour, size, accent, age or appearance.

Representation in books and movies is not about political correctness. It is about recognising that most of us are not superhuman – and that is okay. We can still make a difference, even without superpowers.

I believe the time for traditional heroes has passed. They did a fantastic job but it is unfair to expect our role models to come in supposedly perfect packaging. We need our new heroes to be different – to be more real.

There will be some who are resistant to change. When we meet them, we should take a leaf out of Ms Thunberg’s book. In response to her detractors, she said with superhuman cool: “When haters go after your looks and differences … you know you are winning. I have Asperger’s and that means I am sometimes a bit different from the norm. And – given the right circumstances – being different is a superpower.”

Credit to The National (click here to see the full article).

Ahlam Bolooki discovered her love for books when she was 18 years old though she grew up with her mother taking her to the Sharjah Book Fair each year and was always encouraged to read. The book that transformed Ahlam into a reader was Shame by Jasvinder Sanghera which eventually encouraged Ahlam to read non-fiction struggles of women. Later, she discovered poetry leading her to attend workshops at New York City’s Gotham Writer’s Center, where she studied poetry for several months but also experimented with memoirs, fiction, scripts, you name it! Ahlam finds it difficult to choose a favourite genre as it’s always ever changing and she’s still in the midst of discovering her literary self. She’s catching up on all the gems she missed as a child such as The Little Prince and The Giving Tree, but has also developed a new appetite for Crime Fiction so who knows what’s next?